One of the tasks I'm often entrusted with at the museum, and one of the jobs I enjoy the most, is digging into the history of objects that have recently been donated to NESM or that we have discovered hiding in our archives. This might be researching an individual that we have photos or documents relating to (sometimes with no more than a last name and a vague idea of age), discovering more about an object and how it was used, or even delving into the history of a particular period to understand how it links into the development of the emergency services.

Recently I was handed a bundle of papers that once belonged to a serving Sheffield firefighter, Herbert Hague. Looking into these documents allowed me to uncover some interesting stories from the city's past and served as a reminder of how destructive a force fire can be and how it can dramatically alter the landscape of places like Sheffield.

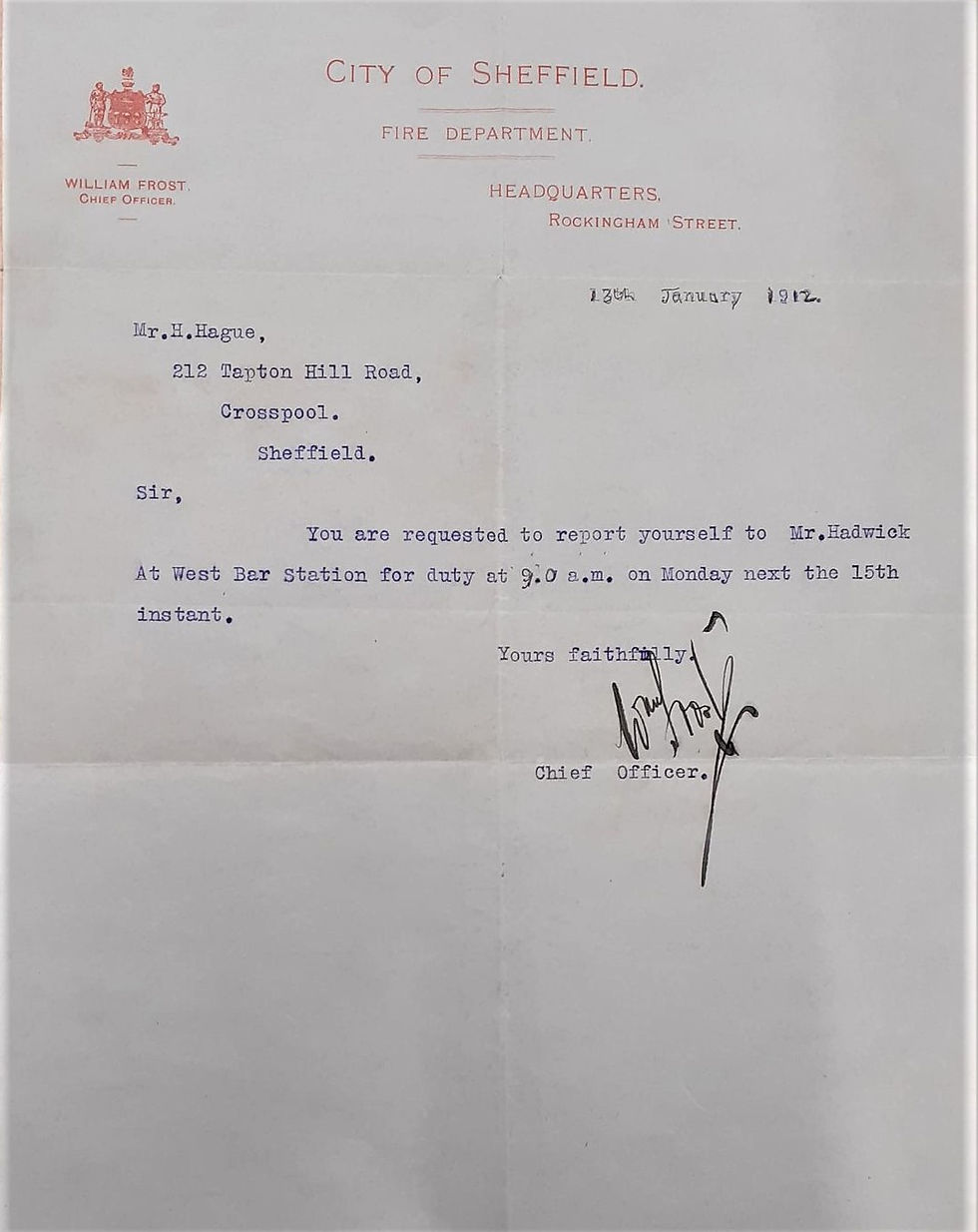

Herbert Hague was a general labourer when he joined the Sheffield Fire Brigade in January 1912, aged 23. A letter in his papers, dated 13 January 1912 and signed by fire chief William Frost, instructed him to present himself for duty at West Bar station - now the home of the museum - the following week.

There was little information to be found regarding any incidents Herbert might have been involved with during his service. This is not surprising given that, in the event, he served for less than two years before resigning his post at the end of 1913. He later served with the Duke of Wellington’s West Yorkshire regiment during World War I, winning the British War and Victory medals, and after the war worked in a snuff mill. He married Irene in 1921, had three children, Irene, Bessie and Eric, and died in 1980, at the grand old age of 92.

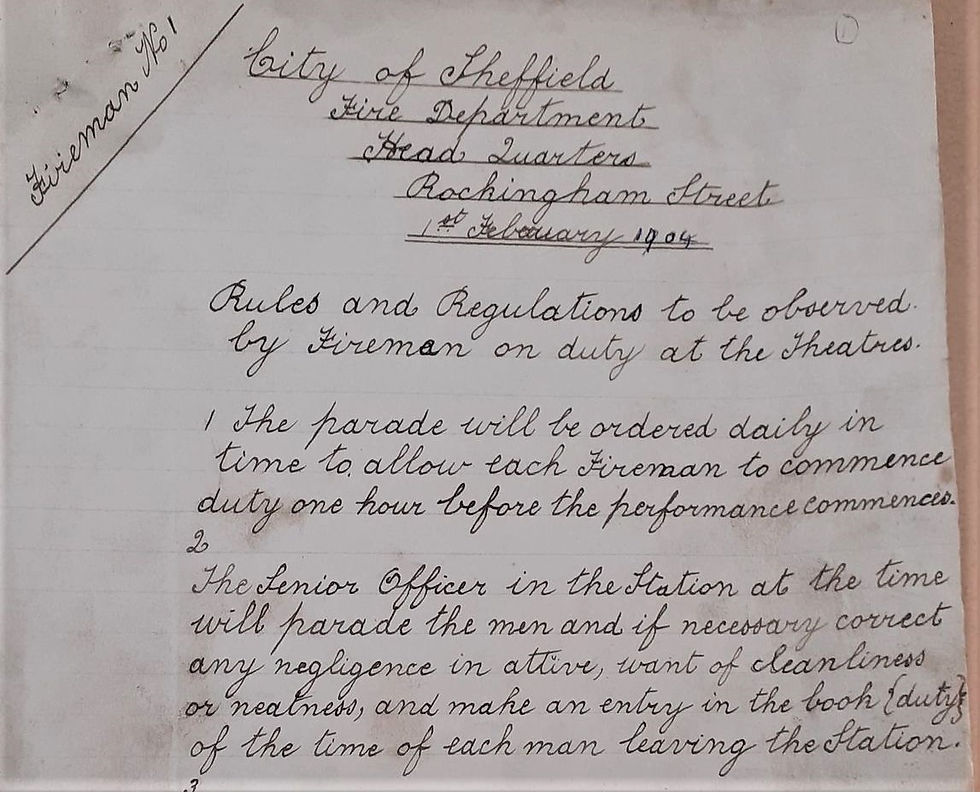

Another document amongst Herbert's papers is a handwritten list of rules and regulations, dated 1 February 1904 and issued from the fire service’s headquarters at Rockingham Street station, “to be observed by firemen on duty at the theatres”. It was looking into this document that revealed some interesting stories from Sheffield's own history.

Some of the directives in this document are straightforward and will be familiar to anyone responsible for fire safety today, like making sure that doors were free from obstruction, equipment was laid out and ready for use and that the theatre was left “all correct” after each performance.

Other rules make it obvious what was expected of the men on duty when it came to maintaining the reputation of the city’s brigade. Before leaving the station they were inspected to correct “any negligence in attire, want of cleanliness or neatness”. Firemen were barred from smoking in the street and, once at the theatre, “any fireman found loitering will be called upon for an explanation”. They were warned off talking to “other persons other than is absolutely necessary” and it was made clear that “visiting the theatre bars on any pretence whatever, public houses either going to or returning from duty will meet with dismissal”.

The documents also include rules and regulations for theatres themselves, as set out by the town council on 29 February 1892. These included making sure gas taps were out of the reach of members of the public and ensuring that equipment such as hoses, hatchets and hooks were always on hand.

The need for these detailed fire precautions is obvious when you consider that by the time these guidelines were issued to Herbert Hague, Sheffield had already lost more than one theatre to fire. In fact, with the combination of wooden sets and backdrops, costumes, props, gas lighting, old-school special effects and plenty of people on site, theatres were always vulnerable to a potentially disastrous blaze; which explains why firemen were on duty during almost every performance and theatres often had their own trained 'fire brigade' to respond to any emergencies.

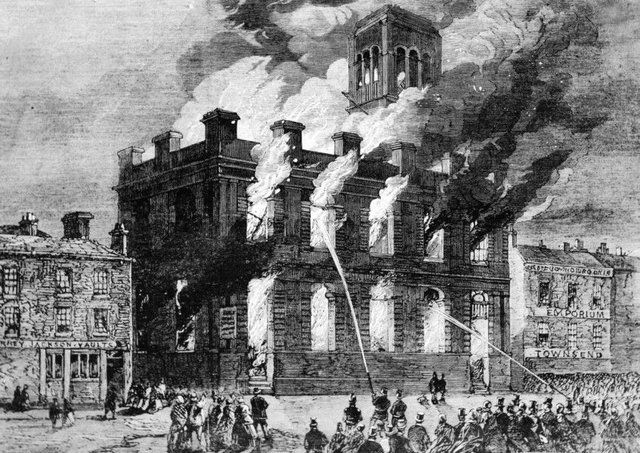

As far back as March 1865, Sheffielders had watched one of their theatres go up in flames. The Surrey Theatre in West Bar - ironically close to where the fire station would later be built - was destroyed in a blaze. At the time the venue was hosting a play called 'Streets of London' that included a dramatic reconstruction of the Great Fire of London. It appears that the mock flames was not properly extinguished and at some point a fire took hold.

Flames were spotted by a passing policemen at about 2.30am. Within five minutes of the alarm being raised fire was bursting through the roof and although the fire brigade was quickly on the scene, it was too late. The resulting blaze completely gutted the building within a few hours.

More than three decades later another local landmark came close to perishing. In 1899 the city’s newly-opened Lyceum Theatre was also badly damaged by fire; ironically, the building had replaced another venue, Stacey’s Circus, which had burned to the ground six years previously. Thankfully it was saved and remains a part of the landscape of the city centre to this day.

Despite these warnings, and the extensive precautions laid down in guidance given to firemen like Herbert Hague, fire remained an ever-present threat and during the 1930s Sheffield would lose two more theatres in major blazes.

The Albert Theatre stood in Barkers Pool in the city centre, on the site that would eventually house Cole Brothers (later John Lewis). Built in 1873, it had been converted into a cinema by the time it was destroyed in a blaze in July 1937.

That incident came less than two years after an even more disastrous event for the people of Sheffield. The Theatre Royal had stood on Tudor Street, opposite the Lyceum, since 1773. By 1935 it was one of the three oldest surviving theatres outside London and one of the most historic buildings in Sheffield.

In the early hours of 30 December 1935 flames were spotted coming from the theatre and the alarm was raised. Thirty firemen were quickly at the scene but the fire had already taken hold, and they had to concentrate all their efforts on preventing it spreading to neighbouring buildings. By the time the blaze was brought under control “virtually nothing remained of the theatre but the outer walls”, reported the Sheffield Independent. “The roof and the three balconies had gone and the stage, scenery and seats in the theatre were reduced to debris.”

The cause of the fire was a mystery. As it was a Sunday there had been no performance for more than 24 hours, and it was the only night of the week when a fireman was not on duty there. Whatever the cause, it marked the end for this historic landmark. It could not be saved and was demolished in 1936.

An interesting aspect of this story was the city's reaction not just to the loss of the building but the effect it had on those who were working there. The Sheffield Independent reported that many artists had been left almost destitute, having lost the "tools of the trade" in the shape of instruments, costumes and other props that had been left in the theatre ahead of the next performance. They had, the newspaper said, neither the funds to replace them nor the means with which to take on extra engagements. Given the disaster, the people of Sheffield were urged to rally round and raise funds to help those left in difficulty.

It's great to be able to dig into aspects of local history like this, and to find out much more than you would expect about your city's past from nosing through some old documents.

.png)

Comments