Grab a cuppa and find a comfy spot because this tale is an intriguing one. It’s a story of shipwrecks, Victorian drama, mysterious tattoos and spooky clairvoyants. If you’re already hooked, buckle up because this blog post is all about the Tichborne case of the 1860s.

In the museum’s treasure trove of wonders lies a dog-eared parchment booklet. To the untrained eye it looks unremarkable, just a few pages of delicate portrait illustrations. But emblazoned across the front page is ‘The Tichborne Album’. This publication is a pamphlet which was sold to the captivated crowds during the trial of the century. Although this is one of thousands of pamphlets produced whilst the Tichborne case was headline news very few survived, making our dog-eared booklet very special indeed.

The Tichborne Album published by the Englishman, a magazine produced by Irish Lawyer Edward Kenealy in support of Thomas Castro aka Sir Roger Tichborne.

The Tichborne case was a cause célèbre that captivated every inch of Victorian society, causing widespread controversy and heated public debate. At the heart of the controversy was a man of many identities.

The Tichborne Baronetcy was based in Hampshire and began in 1621 with Sir Benjamin Tichborne. However the key character in our story, Roger Charles Tichborne, entered the scene some 200 years later. Roger was born in Paris in 1829 into a life full of extensive estates, money and social status. As the oldest son he had a typical aristocratic upbringing and eventually gained an Army commission into the 6th Dragoons. But money can’t buy everything; after his family strongly disapproved of his new-found love interest - who happened to be his cousin - Roger fled England to nurse his broken heart in South America and Mexico.

According to all reports, Roger reached Rio and left aboard The Bella. But it wasn’t long before The Bella mysteriously disappeared, never to be seen again. Only one shipwrecked empty boat was found and as time passed, the likelihood of survivors dwindled.

Despite the Tichborne family and the general public believing Roger to be drowned his stoic mother, Lady Tichborne, staunchly refused to believe her son was dead and desperately continued to search for him. Her hopes were further strengthened by a clairvoyant who claimed Roger was most certainly alive. With this renewed encouragement she began a campaign to find her child. Lady Tichborne placed missing persons adverts and posters in newspapers around South America and Australia, all offering a handsome reward for information.

Lady Tichborne, Sir Roger's mother and strongest supporter of Thomas Castro.

After spending 11 long years waiting for the return of her missing son Lady Tichborne suddenly received an unexpected letter from Australia. The letter was written in rough handwriting and unrefined language but it claimed to be from her son, Sir Roger. Lady Tichborne was convinced of its authenticity and sent for the writer. In December 1866 the writer arrived in London, giving the name Thomas Castro.

The butcher of Wagga Wagga

Back in Australia a solicitor, presumably ‘inspired’ by the large reward on offer, had confronted a client who had alluded that he had unclaimed properties back in England and had been involved in a shipwreck. This client was Thomas Castro, a butcher in the outback locale of Wagga Wagga. After questioning, Castro conceded that he was indeed Sir Roger Tichborne and he had been living under an assumed name all this time. The solicitor wasted no time in getting Castro in touch with Lady Tichborne who had spent over a decade contacting media, producing posters and enlisting the help of organisations like the Missing Friends Office in Sydney. The case of Sir Roger had been everywhere in Australia and they’d finally found their man…or so they believed.

Castro’s initial letter to Lady Tichborne claimed many extraordinary things. His story explained that he’d found his way from the shipwreck to Australia where he’d settled after marrying an illiterate former house maid and having a child. His letter contained many errors regarding his former life but despite this, Lady Tichborne believed her son had come home and was ready to welcome him back into their wealthy family.

Others were less convinced. The ‘returned’ Sir Roger looked significantly different, you see. When Sir Roger Tichborne had left England he was under nine stone, with a long sallow face, straight dark hair and a tattoo on his left arm. The man who had returned had a round face, wavy fair hair and weighed over 24 stone. He also no longer had a tattoo. His apparent physical changes were probably the most obvious issue but there were others.

Top five reasons people weren’t convinced of Thomas Castro:

1. For a start he looked entirely different.

2. He also couldn’t speak French, a language that the Tichbornes grew up speaking fluently.

3. He couldn’t recall what was in a package Sir Roger had left before he went on his trip.

4. Investigations found discrepancies in his story and there was evidence that may have indicated he was actually the son of an Australian butcher.

5. Some of the content of his very first letter referred to facts the Tichbornes couldn’t recognise.

An illustration showing the facial similarities between Sir Roger Tichborne and Thomas Castro.

A clear-cut case?

But despite the evidence suggesting Castro was an imposter he acquired a throng of supporters. At the head of them was Lady Tichborne herself. She had issued Castro with a healthy allowance almost immediately but this, and any other family benefits, were soon cut following the Lady’s death in 1868. The remaining Tichbornes quickly turned on Castro.

Running out of funds and family support, Castro brought a civil case in 1871 to claim the Tichborne lands that had passed to Sir Roger’s nephew. The lands were worth £25,000 and the trial lasted 102 days until the civil court eventually rejected the claimant’s case. Castro’s luck was finally out, and he was arrested and charged with perjury. This criminal trial commenced on 21 April 1873 and lasted 188 days, making legal history for its duration and cost as enquiries had to be made as far afield as Chile and Wagga Wagga.

But before you think this was a clear-cut case…Castro produced over 100 witnesses in his favour, including many of Sir Roger’s fellow army officers who swore that he was in fact the real Sir Roger. Among servants and former servants of the Tichborne family called to the stand was John Moore, Roger's valet in South America. He testified that the claimant had remembered many small details of their months together, including clothing worn and the name of a pet dog the pair had adopted. Roger's cousin also explained that he had accepted the claimant after spending time in his company.

The case also gets murkier when you look at photos of Castro and Sir Roger. Although Castro was much larger than Sir Roger was when he left England there was a similarity in facial features.

‘For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.’

These exceptional circumstances inevitably led to an exceptional court case. It was headline news across the world and, like prominent cases today, it was all anyone could speak about. It captured the attention of celebrities (including Mark Twain who thought Castro was a ‘rather fine figure’ and Lewis Carroll who was enthralled by the case), politicians and society’s high-flyers as well as ordinary people who fought to get front row seats to this unusual performance.

Castro, also known as ‘the claimant’, had a legal team which included eccentric Irish Lawyer Edward Kenealy. Kenealy had previously represented famous poisoner William Palmer and was known for his legal acumen. But this would not save Castro.

The prosecution called 215 witnesses against ‘the claimant’ as well as a handwriting expert, and put forward many scathing theories. Despite Kenealy's defence that the claimant was the victim of a conspiracy which encompassed the Catholic Church, the government and the legal establishment, Castro was convicted of perjury. In just 30 minutes the jury came to the decision that he was nothing more than an imposter. After the judges refused his request to address the court, Castro was sentenced to two consecutive terms of seven years' imprisonment.

The court's verdict swelled the popular tide in favour of the claimant. He and lawyer Kenealy were hailed as heroes. George Bernard Shaw, writing much later, highlighted the paradoxical idea that Castro was perceived simultaneously as a legitimate baronet and as a working-class man denied his legal rights by a ruling elite. In April 1874 Kenealy launched a political organisation, the ‘Magna Charta Association’, with a broad agenda that reflected some of the Chartist demands of the 1830s and 1840s.

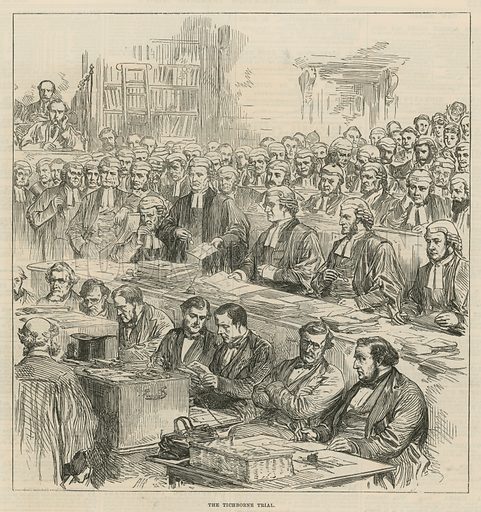

The courtroom during the Tichborne trial.

The Tichborne phenomenon

In the years of the Tichborne movement's popularity a considerable market was created for souvenirs in the form of medallions, china figurines, teacloths and other memorabilia, like the album found here at the museum. Both during this time and throughout the case itself, you couldn’t walk a few paces without being prompted to buy the latest Tichborne pamphlet or broadside ballad. However by 1880, the year Edward Kenealy died, interest in the case had waned. Despite the death of Kenealy the Magna Charta Association continued for several more years, with dwindling support; The Englishman, the newspaper founded by Kenealy during the trial, closed down in May 1886 and there is no evidence of the Association's continuing activities after that date.

Castro was released on licence on 11 October 1884 after serving 10 years. He had lost 148 pounds in weight during his imprisonment and maintained that he was Sir Roger Tichborne. But on release he disappointed supporters by showing no interest in the Magna Charta Association, instead signing a contract to tour with music halls and circuses. The British public's interest in him had largely disappeared so in 1886 he went to New York but failed to inspire any enthusiasm there and ended up working as a bartender.

He returned to England in 1887 where he married a music hall singer, Lily Enever. Eight years later, for a fee of a few hundred pounds, he confessed in The People newspaper that he was, after all, a man called Arthur Orton. With the proceeds he opened a small tobacconist's shop in Islington; however, he quickly retracted the confession and insisted again that he was Roger Tichborne. His shop failed, as did other business attempts, and he died destitute, of heart disease, on 1 April 1898. Before Castro left this world he had one last day in the limelight when over 5,000 people attended his funeral at Paddington cemetery.

Castro was laid to rest in an unmarked pauper's grave but in one final twist to the story, the supposed imposter was buried in a coffin marked ‘Sir Roger Tichborne’, along with a card from the Tichborne family bearing the name ‘Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne’. The Tichborne name was also registered in the cemetery records.

Dangerous imposter or wrongly-convicted heir?

So who was Thomas Castro? Was he in fact a money-hungry imposter? But why leave your job and the country you had called home behind to be potentially humiliated, bankrupt and imprisoned? Or was he a confused and naïve Sir Roger Tichborne, muddled from his exploits abroad and desperate to be reunited with his family?

This case captured the minds of people back in the 19th century and I’m sure it still does today. No one will ever know who Castro really was but having a piece of this puzzling history in our collection is a real privilege.

Thousands of cheap publications were produced specially for the Tichborne case, publications just like our tattered album. They were sold for as little as one penny or sixpence and made to be consumed quickly, similarly to social media today. But thankfully someone decided to save this particular copy of the Tichborne Album, a publication that was most likely in parlours and sitting rooms up and down the country at one time. The album tells us a story about media and communication in the 19th century as well as what everyday people were interested in. It’s also a crucial tool which illustrates the Tichborne case in detail; including the main characters, the narrative of the case and the verdict itself, showing us exactly how people at the time perceived it.

If you’d like to view the fantastic Tichborne album in person feel free to get in touch and arrange a research visit.